The Rise of “Cancel Culture”

“Cancel culture needs to be cancelled!!!” tweeted Tesla founder and now-owner of Twitter Elon Musk on November 30, replying to a CNBC Squawk Box clip about the culture wars and their impact on the billionaire’s car company. The term “cancel culture” has become a favorite among politicians, pundits, and columnists alike. It is ubiquitous; though early articles mentioning “cancel culture” included a definition, the public caught on quickly. The term is now punchy and popular enough to make frequent appearances in the day’s headlines, chyrons, and viral social media posts.

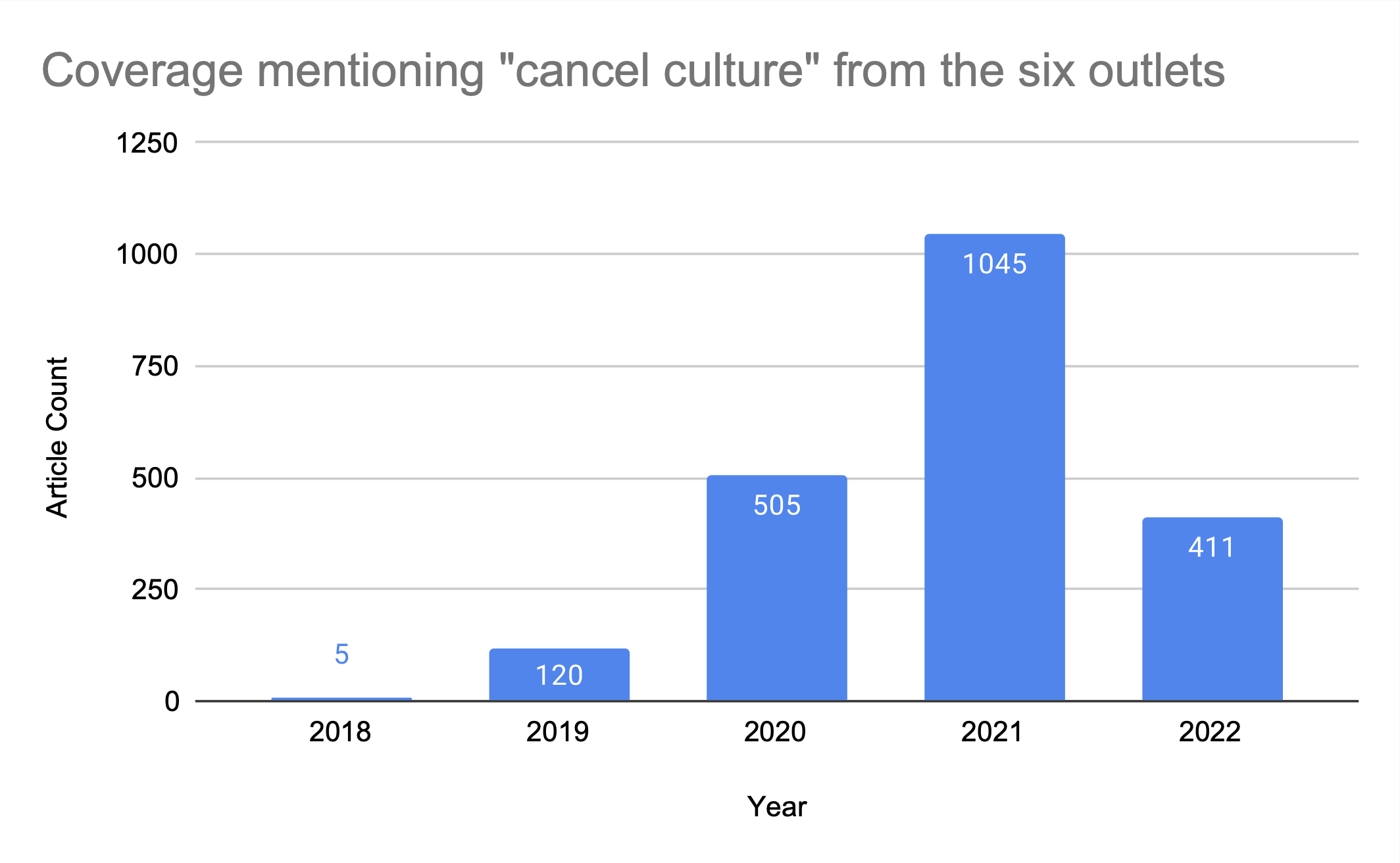

Yet the explosion in the term’s popularity is a fairly recent phenomenon. Though the idea of canceling someone originated in 1980s pop culture — when disco band Chic released the song “Your Love is Cancelled,” according to a Washington Post article — the term did not appear in major national news outlets until 2018. In that year, across The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, Fox News, and MSNBC, the term appeared in just five stories. But in the following year, the term was mentioned in 120. In 2020, the term appeared in 505 stories across the same outlets. And in 2021, the term was mentioned in 1,045 stories from the six outlets.

What, or who, drove the popularity of “cancel culture”? Who is using the term, and how is it being used? To better understand the explosion in the term’s use, I downloaded all articles containing “cancel culture” from the six aforementioned outlets through the end of December 2022.

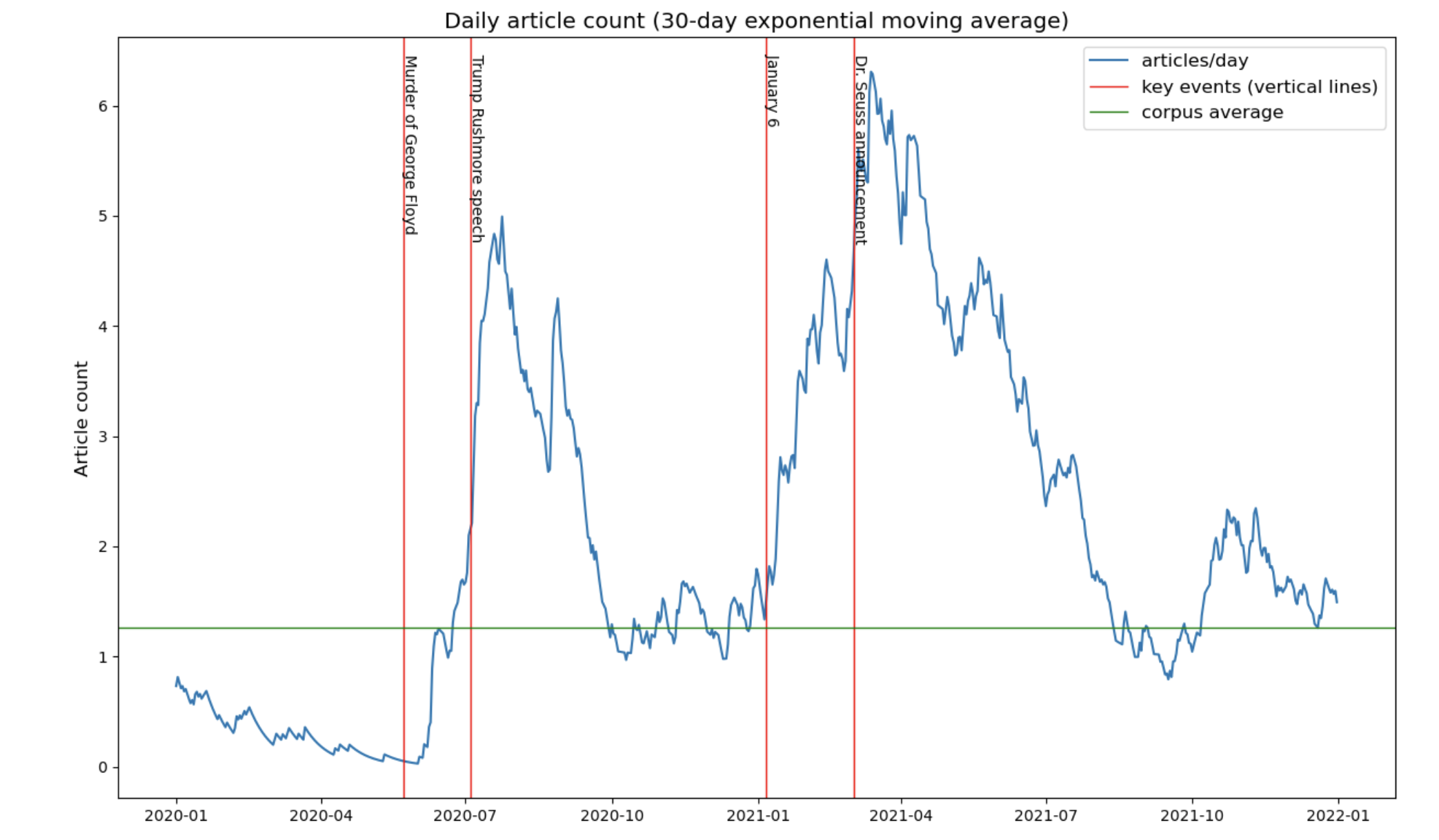

The incidence of the term “cancel culture” seems to increase in times of political and social upheaval. The daily average number of articles or broadcast transcripts containing the term spiked in summer 2020 — after the murder of George Floyd in late May, which sparked widespread protests for racial justice throughout the summer. Articles spiked again following the January 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol.

Occasionally, the “canceling” of a specific individual becomes an ideological flashpoint that garners significant but fleeting media attention, contributing to sudden spikes. One such example is children’s book author Dr. Seuss, whose publisher announced in March 2021 that it would discontinue publication of six books containing text and images considered to be racial caricatures of Asians and Africans. In 2021, more than 80 stories in the dataset mentioned Seuss, and most ran in the same month as the announcement. The news came at a time of heightened media attention to anti-Asian racism due to the pandemic and just a few weeks before the Atlanta spa shootings, an environment that propelled Seuss to become an emblem of the absurdity of cancel culture for the right and left. Pundits took to the media to bemoan the situation or point to it as an indication of progress in the fight against racism. “Who’ll be Left After the Seuss Cancellation?” one March 2021 Wall Street Journal headline asks.

But despite his brief moment in the spotlight, Seuss did not receive much sustained coverage — just four articles referred to cancel culture and Seuss in 2022. Other “canceled” individuals — from Kanye West to Liz Cheney — receive similar patterns of coverage: intense interest that follows a specific incident but that quickly peters out.

So, what are the majority of “cancel culture” articles about? Many articles — 73% — also mention words related to education like “school” or “university,” and 41% contain three or more mentions of these terms, meaning they are likely to focus on education as their central concern. This aligns with the idea that many see academia as the birthplace and primary battleground for the culture wars. The link between the culture wars and academia is made most explicitly by the right; in a 2020 Fox News broadcast, Ben Shapiro connected the two, naming microaggressions and cancel culture as examples of “the censorious ideologically fascistic, top down stuff you’re seeing on college campuses.”

But even more than education, “cancel culture” is closely tied to politics and political figures. Just under 80% of the 2,086 articles in the dataset contain the terms “politics,” “political,” or “politician.” Just under 72% contain terms related to political office, including “governor,” “senator,” or “candidate.” Most articles in the dataset — 59% — are likely centrally about politics, containing three or more of these politics terms. Former President Donald Trump and current President Joe Biden are also frequently mentioned in “cancel culture” coverage, appearing in 1,144 and 1,103 stories, respectively.

It’s clear that cancel culture is politicized, but by whom?

Cancel culture is often tied to a particular political party, with opposition to or “use” of cancel culture described as though it is part of a party’s ideology or platform. In a February 2021 interview with Fox’s Laura Ingraham, Representative Lauren Boebert said, “Really, the Democrat Party is a party of cancel culture; that’s a pillar of the Democratic Party,” explicitly tying cancel culture to party ideology. On the left, columnists and other contributors pointed to Republican opposition to cancel culture as a key part of the party’s platform, sometimes suggesting the party was being hypocritical. The Times’ Jamelle Bouie illustrated how opposition to cancel culture has become a stand-in for Republican candidates’ position on the culture wars as a whole. “Here where I live, in Virginia, Amanda Chase and Kirk Cox, Republican candidates for governor, are running on guns and ‘cancel culture,’ with Chase still treating Trump as if he were the rightful president,” he wrote in his column.

Trump, in particular, has been known to invoke the culture wars — and “cancel culture” specifically — for political purposes. He was associated with the term even in its early appearances in the media; all five of the 2018 articles published across the six outlets analyzed here mention Trump. The former president often invokes “cancel culture” outright, one example being a July 4, 2020 speech at Mt. Rushmore in which he referred to cancel culture as a “political weapon” of left-leaning activists and framed it as antithetical to free speech. His words were then picked up by the media, with dozens of articles mentioning the speech and “cancel culture” published in summer 2020, contributing to a spike in average daily articles during that time period.

This kind of dissemination of the term, beginning with a public reference by a politician or pundit and spreading through media stories about that person, is not uncommon. Trump, Kanye, and Musk have frequently railed against cancel culture, and their words have been repeated by the media in quotes or clips. (Fox News ran an entire article about Musk’s tweet in reply to the Squawk Box segment.)

But despite the rapid rise of “cancel culture” and its popularity among public figures, the 2022 data for the term suggests it is falling out of favor, at least in the mainstream media. Over those 12 months, the term appeared in just 411 stories from the six outlets, a steep decline from the 2021, or even 2020, numbers. Perhaps the drop is a result of the weakening of Trump’s hold over US politics now that he is more than two years out of office. Or perhaps there are simply too many other culture war terms jockeying to take its place.

–Abigail Chang

Methodological note: I examined 2,086 stories mentioning the term “cancel culture” in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, Fox News, and MSNBC from January 1, 2018 through December 31, 2022. Cancel culture is sometimes written in quotes to help distinguish between “cancel culture” the term and cancel culture the phenomenon. For additional information regarding our methods, see here. Photo credit: Robin Jonathan Deutsch, Unsplash.